Owls I

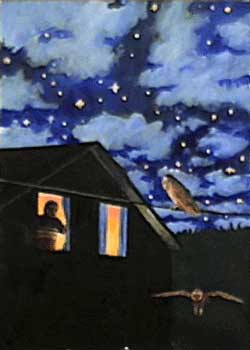

I once heard a scream more alien than a human scream, A few feet above my head A terrifying screech of the sort that echo in myths and horror stories. I should have realized then that myths and horror stories are exactly that, stories and myths and----nothing more. Myths magnify and project human concerns and fears. Reality is not an exaggerated human emotion. Owls are different than what my culture taught me about them. Once I got over my fear I looked up and found the source of the frightening sound to be a lovely, ghost-like bird illuminated under the street lamps. It is a softly feathered bird, its feathers hushing the air around it so that it flies in total silence. Its back is darker, ochre and orange in a good light, but covered, as it were, with tiny star like designs. At twilight, if there is still some light left, these delicate designs can look like a starry sky. It is a bird that wears stars on its back. It was a Barn Owl. It was right outside my window

Over the next few night I stayed up to watch the Owl fly into the barn opposite my place. I learned there were two Owls and they had a nest. The parents wanted to frighten me from their nest and that was the meaning of the scream. I realized that their protection of their young was quite justified and I was the intruder. So I respected their wishes and stayed away from their nest area. During the day when they were sleeping I examined their pellets, regurgitated bones that they expel. Mostly they were eating mice, voles and perhaps woodrats.

At first they resented me watching them from the window and would place themselves on a loose plank atop the barn and leap up on down on it while looking at me and flaring their wings, swiveled and angled forward, in a menacing grimace. The board slapped on the barn roof and was louder than a beaver slapping its tail near a lodge, which itself can be quite frightening. But the combination of the slapping board and the exaggerated threat posture of the Owls was truly intimidating. But at the same time, I admired their intelligence in knowing that the board would make a loud noise and they directed the noise at me. “Go Away” they were saying.

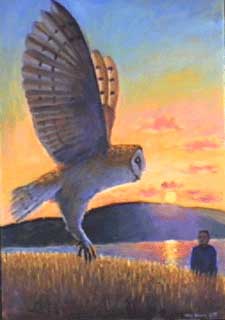

During the following weeks I spent many nights up trying to accustom the Owls to my presence. I moved outside and sat for hours--- first very far away and then the next night a little closer, and the next night closer, until at last they grew to know me and trust me a little. After a week of slowly getting closer they accepted me to within about 50 feet of the nest site. One night I sat on the ground 50 feet from the nest. One of Owls flew across the barn-yard straight toward me, slowing as it reached about twenty feet away. It continued to fly toward me slowly, very slowly, nearly drifting at my eye level. It got larger and larger as it come closer and began to fill my whole field of vision. It came within a few feet of my face and looked me straight into my eyes. I was completely astonished at its trust and bravery. I was not afraid of it and it could plainly see this. It saw that I was no threat, and I saw into its eyes. Trust.

"Contact, Contact… who are we, where are we?”

Henry Thoreau exclaimed, recalling the wonder of his experience on Mount Katahdin

in Maine.

I had come into direct contact with a wild Owl. The mystery of existence is amazing. ”Talk of mysteries”, Henry exclaims

“daily to be shown matter, rocks, trees, the wind on our cheeks....the actual

world". Yes, the actual world is mysterious and marvelous. The Owl taught me that my conceptions of Owls were all false. The reality of them was far more marvelous than I could have imagined. Owls are not spirits or omens, fearful predators or symbols of wisdom. Their existence is enough for me. It is mystery enough to have contact with the glittering brown eyes and white face of an Owl at midnight, looking at me with intense recognition and acceptance. It was a profound moment in my life to have seen this deeply into a wild birds eyes and realize that its world was quite as valuable and important as mine. The bird had honored me with its trust, and looked into me with a look I will never forget. From then on they did not threaten me and I began to learn about these wonderful birds. I watched them nest for two years and learned all sorts of things about their habits, sounds, what they ate, how often and what the fed their young, and what devoted parents they were. I managed to save one the fledglings, which had clumsily flown into a telephone wire on its first flight--- all birds are clumsy during their first flights-- and had fallen nearly unconscious onto the ground. A few good people of that town had gathered around the fledgling and wanted to carry it away to a bird shelter. They meant well, but I stopped them, and insisted they leave it alone, and shortly it got up and flew off. Safe from the cages of the human world. I saved the nest from boys too, who wanted to pelt the birds with stones. The Owls were my nighttime companions for two summers, I usually would go walking the hills near the Bay or the Sea when there was a full moon and on those occasions I would sometimes hear them clicking their clicking sounds to one another. The land under the full moon always seemed resplendently drunk and a little out of kilter, a little crazy, or nearly electric in the half-light of the moon. Looking up at such times, I would occasionally catch a glimpse of them against the Milky Way glittering above. There was something like a clown’s white face in their demeanor, yet at the same time they were deeply serious, aware and intelligent. Yet, because many people fear them and have misconceptions about them, I worried about their fate.

One day I found one dead in a remote hilly area not far from the ocean, the carcass eaten and its feathers scattered over an area. I was sure it was a Great Horned Owl that killed it, and I was angry at Great Horned Owls for months. There was no reason to blame the Great Horned, of course. It does what it feels it must. I once saw one try to attack my cat, who luckily escaped. But there is more to Great Horned Owls than killing. I once got to witness their very lovely pre-mating endearments. They are very affectionate with one another at that time. chasing one another and rubbing beaks together. They are also good parents and I have seen them catching food for their young. But I was angry they killed the Barn Owl, and did not forget it soon. I lived across from the Owls for three years and for one reason or another decided to leave that area, with deep regret. One night I went out to the hills to say thank you to this area of Northern California, promising that one day I would return. There was a reconstructed Miwok village there and I went there to express my gratefulness. The Miwoks and Pomo were the Indians that had lived in that area for many thousands of years, and I felt that such a place, that honors them, would be a good place to say thank you to this land that was deeply part of my heart. Under a full moon, I found myself talking to the trees and clouds, the earth and the sea, remembering all that I had learned about nature in this magical place. After I was done saying thanks, I turned around and not more than twenty feet from me, on top of a redwood bark typee, the two Owls that I had watched and lived next to for two years were sitting shoulder to shoulder and looking at me. It was as if they had come to accept my love and thanks.

I returned to this area in Northern California some years later to find that the barn where the Owls lived had been altered by the good people of the town and turned into a little shopping mall with a big parking lot. The Owls had been displaced. I went into the stores and tried to explain to the owners that they had taken the place where the Owls lived and should make some effort to recompense the Owls, by building some Owl boxes on top of the refurbished barn, for instance, and thus encouraging their return. None of them seemed to care that that they had stolen the Owls home, and not done anything to recompense them. None of them seemed interested in the Owls or their loss. It was as if the Owls never existed and only people and profits mattered. All they cared about was making money and their own lives and did not care at all that the barn Owls has become locally endangered in many areas precisely because humans are so insensitive to the lives of other species. It occurred to me that extinction is first and foremost a disease of the human mind, and that those animals that disappear from the earth due to human ignorance were first killed by the closed minds of people in our own society.

Copyright © 2002 Mark Koslow. All Rights Reserved. |