|

Canada

Geese III

Some Observations on a Geese Community

For a human-animal

to come to know another kind of animal, particularly a wild or non-domestic animal, is

extremely difficult. To know a non-human animal, bird or other natural being

requires patience, selfless watching, admiration, indulgence, open mindedness,

listening, a willingness to trust, and ultimately a willingness to love.

It is much harder to come to know a wild

being than it is to know another human. Wild birds, snakes, mountain lions,

foxes, wild forests and deserts are so far outside human concerns and interests

that they are much harder to get to know than speakers of a foreign language,

people of another race, class or ethnicity. It takes much more time and

dedication, even reverence, to get to know wild beings. Love grows slowly, and

requires great amounts of time to grow. This is the primary reason so little is

known about wild animals, birds or beings in the sea. Few will spend the time,

few care, few even know that such radically other and wild and hidden lives

exist. Wild birds and animals exist in almost another dimension than humans. The

failure to learn about and be sensitive to their lives is now having disastrous

consequences on many species. Human ignorance, malice, fear and myths and

falsehoods about animals and nature abound, and little has been done to correct

this sad fact.

I have heard farmers say that they never

name their domestic farm animals because they are going to kill them, and not

naming them makes the killing easier. This shows how much human emotions are

locked inside language as a system of cultural and emotional control. Naming the animal to be killed somehow

gives the animal a more sympathetic value to the farmer. Not naming it makes the

animal foreign, other, mere future meat for the table. Depersonalizing an

animal makes it easier to kill it. Impersonal study also creates distance and

alienation, and this is one reason science has contributed to the

destruction of of nature. The degree to which humans impersonalize and distance

themselves from animals and nature partly because humans are trapped and alienated by their own language.

Wildness is in the realm of the unspeakable, the ignored, even the shunned. Human

languages are cultural prisons, in a way, because they are abstract, and have

lost touch with a concrete and direct experience of non-human worlds and ways of

being.

One must abandon the cultural conceit that human

language is superior to other forms of communication. One must stop listening to

the words in one's head and listen to the wordless wonders being expressed all

around us in nature. Real looking at the world of non-human beings

requires trying to stop one's thinking in terms of human concepts, culture and

languages. One must unlearn such absurd beliefs as the conceit that humans have

been given "dominion" over the earth, or that humans are "made in god's image".

Wild geese, like pristine forests, need no "stewards", landlords or gods. The

suggestion that mankind "owns" or has dominion over ravens or eagles, ospreys,

forests, lakes,

elephants or foxes is laughable.

One must learn to value

and prize the rebellious arrogance of wild things. Their arrogance is their

freedom from us, their fierce devotion to their own lives. Wild things despise

the mere suggestion of human "stewardship" and "dominion". The Acorn Woodpecker

has its own 'dominion', thank you, as does the Flicker and the Beaver. Wild horses will not

willingly submit to human self importance, nor should they. I have never quite

been able to admire the human domination of horses or horse racing nor the

myraid other ways that humans "tame", "break", domesticate and abuse other

species. The falcon screams freedom, and the lion

despises his cage, and the polar bear must have his freedom to range across

thousands of miles of snow. Even the chickadee's sounds express fierce

opposition

to human control, capture and limitations. Natural beings have their own

integrity, their own notion of rights, their own culture, their own ways of

seeing.

If one

would know animals one must abandon most of what one was taught in

schools. Indeed, young children, prior to adolescence, usually have a

strong affinity with animals and nature, and come to understand much about them

easily. This affinity appears to be innate. This sympathy is often destroyed in most

children by the time they are

past adolescence, unless an adult supports their interest in nature of animals or

they simply refuse to accept the cultural conditioning against nature and

animals. The culture

teaches children by example that there is an impenetrable wall separating nature from the human

and that humans are superior and that nature exists merely for human use and

domination. This is the lie of "speciesism", and a very effective lie, much

like the lies of racism and sexism. To unlearn the cultural prejudices one must

give up being influenced by speciesist cultural expression, often conveyed

variously in religion, on T.V., in books and through business and government.

Then one must learn to listen as possible to the voices of the cultures in nature.

Natural communities do express their own cultural norms and values. You must let animals and birds "steward" and

guide you. You must give up your culturally determined need of power, of being

ascendant, superior, and better than nature and animals. You are not better, and

not superior. Revere them and grant them their freedom and their independence

and they will begin teaching you who they are. They might even begin teaching

you who you are.

So, with these general observations in mind, which I have learned from watching

many different birds and animals in their natural settings, I want to talk

here, on this page, about just one kind animal or bird: Geese, specifically, Canada Geese. They

are extraordinary beings, quite as amazing and full of variety and wonder as

human beings. In some respects they are an improvement on human beings, and

certainly their devotion to each other, to community, to their young, and their

spare and effective use of their own non-linguistic language has much to

recommend it over human cruelty, was, greed, selfishness and need of power.

When I first started

studying them some years ago, I could only grasp very simple things about them.

I became aware that my culture had taught me nothing whatsoever about them,

other than that they migrate. Indeed, my society had taught me virtually nothing

about the natural world that is all around us. Nearly everything I have learned

about it I have learned on my own. The society I grew up in had built a wall

between me and the natural world made of prejudice, hatred, willful ignorance,

neglect, will to power, greed and speciesism. I wanted to climb over this wall

of ignorance, as I had done with other animals and birds and with nature

generally. I knew that climbing over the wall that separates nature from

Euro-American society would make me somewhat of an outsider to that society.

I knew that by climbing over the wall, I too would have to learn to live in a

threatening environment, as do threatened species and indigenous cultures. There

are perils in siding with the victims, outcastes and neglected who live outside

our societies. There are perils in siding with beings that our society abuses

neglects or treats with malice or indifference. One becomes a sort of

sensitive coyote, wandering outside the walls of the town, wary of all the

dangers that come from the town. One becomes aware that a whole different way of

living and being is not just ignored by the people who live behind the walls of

the human city, but that the way of nature and animals is largely hated by these

people, and they want to exploit it, destroy it, limit or abuse it for their own selfish interests.

I knew Canada Geese were beautiful birds and had watched them flying with wonder and

admiration. I knew some people despised them for their droppings, which has

always struck me as hypocritical. Canada Geese droppings are small and dissolve

in the rain, and are hardly a health danger, whereas human droppings, waste and

garbage are

everywhere and pollute whole rivers and ecosystems. So I already knew Geese were

being scapegoated by human hypocrisy and that in many towns and cities they were

being killed. Those who scar the land with golf courses, cattle, parking lots,

strip mines, air pollutants, clear cutting and

shopping malls did not like Geese walking on their manicured grass. So they shoot them.

Hunters kill them for fun and the feeling of power it gives them. Yet the same

society that targets Geese, and many other animals, knows virtually nothing

about them. Ignorance and malice often go together.

One of the first things that endeared me to Geese

was seeing their goslings. The goslings are a pale yellowish and green, almost

the color of a new grass shoots, or the emerging petal of a daffodil or a new

leaf just beginning to spread out from a bud on a tree. Yes, the color of

goslings is the color of spring, the color of new grass, new leaves, new flower

petals. Their young feathers shine and glisten in the sun.

They usually hatch from their eggs in May, in the area where I live, and the

solicitousness of their parents impressed and amazed me. Their parents are

highly protective of them and the female will often lift her wing slightly and

let them gather under her wing for warmth and security. They go under her wings to seek

shelter from the storm, and they rest there at night. She covers them to keep

them safe for predators. With a gentle sound from her, I have seen them

all scurry under her wings where it is safe. The gander, the father of the

goslings, stands watch over the little ones and their mother, very proudly, his

strong neck raised high and looking about in all directions, guarding and

protecting them all.

NESTING SPACES and the COMMUNAL WEB

Nearly

anyone who remembers their mother can recall feeling the need of her protection

and safety, and who, as it were, took one under her wings as a child. I have

even sought safety and refuge, on occasion, under the wings of my mother as an

adult. Then, with the passage of years, as she grew weak and confused, I took her

under my wings and sheltered her from harms as best and as long as I could.

My own mother helped me understand something of the intimate lives of Canada

Geese and just how much their lives share essential things in common with mine.

But

I am getting ahead of my story. I had watched geese in many places and had grown

increasingly fascinated with them and their behavior. But I had not yet found a

nesting site where I could watch them more intimately. I finally did find such a

site at Hero's Wetland, the same place where I had been studying Orioles and

other birds. The first pair I watched nest lived almost immediately under the tree where Hero, the baby Oriole, had been born and the next

year they nested again in the same group of trees. I called the pair Hero's

Geese, since they nested on the little peninsula where the Orioles had nested two

years in a row.

I watched the Geese intensively for about

three years, less so in recent years, since we moved away from that area. The

first year I watched them was a constant marvel. Hero's wetland lies along a

river, and is periodically flooded by the river, usually in spring an early

summer. This, along with rain, sustains water levels in the Wetland. Some years, when

there is less rain, the wetland has dried out in August and early fall, although

not for long and never entirely, such that the frogs and turtles are able to

return for the next season. The total population of Geese in the Hero's

flock was about 90 birds in August or September. This number appeared to be

diminished by the following spring to 60 or 70 birds. I puzzled over what

happened to the 30 or so birds who were missing after their migration in the

Spring. I suspect hunting had something to do with the loss, as they migrate out

of the safe, non-hunting area where Hero's Wetland is located. Also, I believe that some of the young

birds, yearlings and two year olds, leave the Hero's community to join other

communities.

Hero's Geese, I figured out, after watching

them nest over two years, where something like elders in the community. They

were very successful at nesting, unlike some of the other pairs, particularly the

younger ones. Hero's Geese managed to enable all of their eggs to survive. They

had three goslings some 30 days after the eggs were laid. I watched the female

nest most of the days of this period and she was remarkably faithful to her

nest site. The more time I spent near her the more I admired her abilities. She

was extremely gentle and tender with the eggs and turned them often. She pulled

down out of her own breast to soften the grasses in which the eggs lay. The soft

down feathers were lilac in color and on colder days, when she would feed in the

wetland a short distance from the nest, she covered the eggs with the down and

grasses. On unseasonably warm days she visibly suffered sitting in the sun. But

she was devoted and endured. Her husband, the gander, was always near her,

protecting her, watching out for dangers, attentive. He would watch the

nest more closely when she left it to feed. Their communications were

quite complex, unlike what the bird books say, which describe Geese

communications as being elementary. But the female would often alert her husband

to another goose approaching before he saw it. In other words, she was quite

able, through carefully modulated sound, to direct his attention to an incoming

danger. The offending goose or geese were usually one of the yearlings or

two year olds. He would chase off the interloper, sometimes with her help.

Once this was done the pair would make sounds toward each other,

as if reaffirming their commitments to the nesting area and to each other.

During events like this, the communications of the Geese were quite complex. The

ability to influence the minds of others is supposed to be a trait of "higher"

species, like Dolphins and Orangutans and humans. But the notion of "higher"

or "key"

species is a self serving, anthropomorphic projection. Most humans

underestimate animals and birds, as well as nature generally, while they vastly

over estimate their own importance. This underestimation of natural beings

is built into the sciences. The Geese I watched were quite able to communicate

very complex things to eachother, in ways that were both simple and beautiful. I

sometimes found myself wishing that my own language could be as direct and

unambiguous as the non-linguistic language of Geese. Human communication is very

cumbersome and has many faults built into it.

On one occasion, where I was watching a different community of Geese a

few miles up river from Hero's, I saw a group of ten or twelve Geese try to stop

a raccoon from eating eggs out of one of the nests. The raccoon was already on

top of the nest, and apparently the mother and

father of the nest had been too far away to defend it soon enough. They failed

to stop the predation. But in other cases I believe the Geese succeeded by group

efforts of this kind. There were many Raccoons and a Fox at Hero's and some of

the nests were destroyed by Raccoons. I witnessed one such event and the loss of

the eggs was due to the parents, who appeared to be young geese, having spent

too long a time too far away from the nest, allowing the raccoon an opening to

steal and eat the eggs. On another occasion I found the recently eaten carcass

of a goose, apparently killed by the fox. But this was only one example. The fox

was often around and it managed only to get one goose. So the

Geese are apparently quite able to keep themselves safe from Foxes, most of the

time. I believe they also can fend off raccoons if they are vigilant enough, and

saw the Geese harassing Raccoons a number of times. I

watched once when a red Tailed Hawk landed in the branch of a tree above a goose

and a gander and their four goslings. The parents saw the Hawk and called the

goslings under their wings, and looked up at the Hawk with threatening postures,

honking. The Hawk gave up his notion of eating the goslings.

There are various hazards to nesting on the

ground. Foxes, Raccoons and Hawks are three such hazards. But there is also the need to

keep the eggs warm. Young nesting geese, who appear to be inexperienced, sometimes stay

away from the nest too long and the eggs die from exposure, becoming too cold. A

few of the nests at Hero's failed for this reason. In addition, sometimes nests

fail because the eggs are

sterile. Nesting is certainly in part a learned activity, and once of the

valuable things about the larger nesting community at Hero's is that the older

Geese, who are more successful at nesting, provide an example of how to deal

with the hazards of nesting on the ground. This was demonstrated to me over a

number of years, when drought and human alterations in the environment caused

the water levels to differ sharply from year to year. The geese responded to the

loss of eggs in resulting from these changes by building different kinds of

nests over different years. For instance, before the more recent higher water

levels, the geese tended to nest on peninsulas and the two or three islands in

the pond. But when water levels rose above what was safe for nesting on these

islands and some nests failed the geese clearly thought out the problem and came

up with solutions by the next year. So now there are new kinds of nests at

Heroes. One nest is on a 5 foot height stump of an old sycamore tree that has

fallen, Other nests are on top of fallen logs in the water. One goose

built her nest up out of the water of reeds and bog grasses, and very good idea

since she can raise the nest to the height she wants it by augmenting the

grasses.

There are other threats to the community of nesting Geese

besides other animals and rising water levels.

Occasionally, I would see a pair or group of Geese of unknown origin fly into

the Wetland and this would cause trouble, with the result that the gander of one

of the nest areas would chase off the visitors, head down, threatening to bite.

Most of these threats are quite harmless, and rarely resulted in an actual bite.

I only saw a truly violent confrontation between the Geese twice. Once when a

goose got in between a gander and its newborn gosling. The gander saw this as a

real threat to the goslings and was very vicious in chasing off the other goose.

The worst occasion of violence that I saw was between

two nesting ganders of Hero's wetland-- two Geese that were probably

related and nested 50 feet from each other. The circumstances were these: there was an especially violent and heavy rainstorm about midway in the nesting season. The

river was much higher than usual and flooded the wetland, raising the water level

more than a foot. this resulted in drowning a number of the nests. All the eggs

were destroyed in these nests. I arrived at Hero's while the storm was still

raging. One of the pairs of Geese whose nest had been lost had left the

nest site with his mate and they had crossed into the nesting area of another

pair. The gander who lost his nest attacked very viciously the gander who did not

lose his nest. It was an extremely violent attack and probably resulted in some

injury, though nothing bad enough to be visible. It was very clear that the

goose that had lost the nest was extremely distraught from his loss.

Geese certainly have emotions and complex psychological reactions to stress,

much as humans do. The attack on the goose who did not lose his goslings was clearly born of

frustration and

anger. With humans, suffering and extreme hardship produce similar

reactions. In areas where there is poverty and over population, stress levels

increase crime rates and violent altercations. It is the same with Geese. The

storm ruined many nests, and this produced frustration and anger in the Geese

who suffered the hardships. The gander lashed out violently against his nearest

neighbor, who may well have been his brother or cousin.

One of the saddest events I witnessed with the Geese at Hero's was

watching a young female who sat on her eggs over 40 days. Generally the eggs

hatch out by 35 days, but in this case it did not happen. She kept sitting on

them past their due date. She became visibly distraught and nervous about the

eggs. When Geese are suffering from the heat they open their mouths slightly and

appear to pant somewhat. This goose was doing this while she sat on her

nest. But more than this, she began to pace around the nest, pulling out grasses

with her beak and tucking the grass under her rump behind her. She did this in a

circular fashion, walking a few steps around the nest, pulling up grass, tucking

the grass behind her, walking a few more steps and doing it again, and so on, in

a circular path around her failed nest. The pulling up and tucking behind of the

grasses is what they do when they begin to build the nest. So it appeared that

this goose, having sat on her nest over forty days, with the weather becoming

increasingly hot, had become nervous with worry, and she expressed this as a

neurotic imitation of nest building activity, but the activity had no purpose,

other than expression of her frustration at the failure of the nest. It was a

very moving thing to see and I wished I could have helped her somehow. I felt a

deep compassion for her plight. She worked so hard to bring her little ones into

the world and they died in the eggs. It was very much as if a woman who lost her

child, nevertheless continued to prepare for its arrival, buying the expected

one clothes or a crib. But the child was gone and she could not face the fact.

It was very clear that the goose that had lost the her babies was extremely

distraught from the loss, much like the gander I saw who became violent after

the storm destroyed his nest. In both cases the tragic nature of the events

resulted in extreme reactions in the emotional lives of these sensitive and

wonderful birds. They take nesting very seriously, and the loss of a nest is an

occasion where their suffering is visible and acute.

I never saw any evidence of outright cruelty among the Geese,

though they could be severe with each other when there were conflicts. But there

is nothing like the malicious and cruel ignorance and violence of which humans are capable.

One day I found some human adult footprints leading up to a nest, and the nest

was destroyed and the eggs were gone. It was an act of malice, that had no other

point than mindless destruction. On another occasion, I saw two teen age boys

about to hit the Hero's Geese female with a large stick. I had been watching her

for weeks and she had grown accustomed to me. But I never went closer than

twenty feet to the nest and never approached the area at all without a discrete

announcement that i was coming.. These boys were about to hit her across the neck

with the stick. They probably would have killed her. I screamed from a distance

and they stopped. I saw the same young man on another occasion trying to harm

frogs.

Geese do not have this tendency to malice and

cruelty. Their communities work marvelously well, and the only real threat to

their well being is humans.

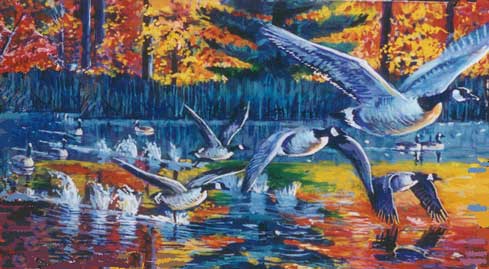

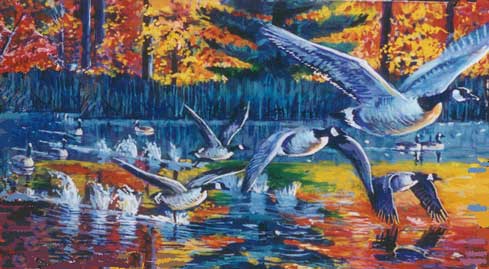

Part of the Community (detail)

COMMUNITY NOT "TERRITORY"

One thing that became

clear very soon after I began studying Geese is that they do not have

"territory" in any sense of ownership. Mallards, other ducks, small birds,

herons, muskrats, turtles and frogs, among others, regularly crossed or shared the

nesting area. Even some Geese were allowed within the area, within certain

limits. The relation of Hero's Geese to other pairs of Geese nesting in proximity to them was

close and cooperative for the most part. The nesting Geese joined together to

face common threats. I began to see that what I was looking

at was not an isolated pair in a territory, but a community of complex relations. There

were many nests at Hero's Wetland. The

whole notion of their being territorial boundaries, in the sense of ownership of

private property, or discrete nuclear families in competition, disappeared. This

notion of territorial natural selection is a projection of capitalist values on

the natural world. The projection dissolves on closer examination.

What the Geese were doing was not defending a

territory, but preserving a lattice of communal relations in the nesting area and doing so

only in regard to the safety of the nests. The proximity of many nests in the

same area, each joined to the others, and each separated by a boundary of

respect, established a kind of web of relations among all the nesting pairs. The

Geese community consisted of interlocking cooperative nest areas. There were

clear relations and alliances between the various families.

Any pair that made certain honks because of a threat was often echoed by the

nearby pairs, who also became concerned about the threat. They would sometimes

join in on the chasing away of the interloper, and the severity of the

expulsion of the offending goose appeared to depend on what the relationship was.

Geese from different flocks who landed at Hero's Wetland appeared to be treated

more harshly than Geese from

the Hero's flock. What initially appeared to be separate territories was actually an

interlocking web of cooperative nesting spaces, each one an expression of a larger communal

relationship.

The notion of territory is a dogma in

evolutionary theory and ornithology. But I started doubting its validity because

of what I saw the Geese doing. The Geese

were not creating territories, but life spaces, a nesting community, a communal

web of nesting spaces, and the

apparent arguments between geese were something much more complex and

interesting than the mere assertion of capitalist values, land rights or ownership

or competition among nuclear families. A flock of Geese is a cooperative colony,

not a bunch of separate family units of obsessed with their own advantage and

territory.

The reference of most of the behavior of Geese to the larger community is constant across the

spectrum of their lives. Even in the mating ritual, (described in the poem

"Coats of Liquid Light") , the Geese often call out after mating to the rest of

the flock. "We have done this" they seem to be saying. Moreover,

even before they begin mating, the Geese pairs chose out an area where they will

nest. The mating goes over days and even a week, often many times a day.

There is thus a close attachment not only to each other

but also to a place. One rather humorous detail of their attachment to place and

the relation of other species in the area to the Geese is the following. A pair

of Geese I was watching mate were observed by a pair of Blue Wing Teals, a kind

of duck, who had the odd habit of mating at Hero's Wetland over some weeks but

then leaving to nest elsewhere. This pair came to Hero's every year to do this.

One day I watched the Geese mate and then the Teals mated on the

exact same spot, no more than a minute after the Geese had ended their mating.

It seemed the Teals not only had a certain respect for the mating of Geese, but

they chose to imitate the act, even down to the choice of spot!!! The Geese had

created a congenial environment not only for themselves, but for other species

too.

Interspecies affection is an interesting subject. I suspect that there is much

more interspecies

interactions and awareness than human- animals know about. There is a

tendency to see "affection" among

animals in human terms-- which may be a mistake. These two Blue Wing Teals

return to mate in this pond every year-- they do not nest in it, but apparently fly further north-- but there is

clearly a relation of the Teals to the Geese

that has an "affectionate" dimension-- though the exact nature of this affection

is hard for humans to understand-- it is a

relationship that is subtle and profound enough to move the ducks to mate not

only in the same wetland as the geese but on the same spot. There are many things

in nature that simply are not noticed by humans because of our tendency to see

things in human terms. Mating on the same spot is not something humans are

likely to do-- but it appeared to have great meaning to the Teals.

individual pairs of Geese have

a strong bond to one another, but this bond is closely allied to another bond

they share with the entire community

of Geese. The shape of the community is clear by late summer and into the

Autumn, when the young begin to learn to fly. Then one can see clearly that the

separation of pairs and defense of the nesting area of each pair was a temporary

phenomena, which was not about "territory" at all but rather about preserving the

integrity of each nesting area within the larger context of the whole life of the Geese

community.

The transient nature of the nesting

spaces created during the period of sitting on the eggs is shown when the eggs finally hatch. I was able to

witness what happens

after the egg hatching with many of the pairs. The first year there were seven active nests around the wetland, with more near

the river, and some more in an adjacent floodplain forested area. The

second year there were nine active nests around the wetland alone. The third year

the numbers were similar. Of these I was able to see the first

days of the goslings of numerous pairs. In each case, the parents

lingered near the nest for the first day, while the little ones learned about

the elements, experienced swimming for the first time, and how to eat. But

within a short time, no more than a day or two, the parents abandoned the nest,

and led the goslings first toward the woods and then toward to river. I was amazed that all the families I saw do

this went in the same direction. They first headed toward the woods, where they

might stay for another day or two, eating vegetation, and then they would go

south toward the river.

The Geese of Hero's Wetland on The River

( details of Barn Swallow painting)

Moreover, once the nest site was abandoned, arguments between pairs and other

geese cease, for the most part, if not entirely. Within a month, as the birds go

into their molting cycle, the Geese and gosling merge into a group again. In

fact they always were a group, and not separate pairs in a "territory".

The separations were merely apparent.

Once the birds leave the nesting area with the

goslings the flock could be found down at the river. The flock would fluctuate in

size, some pairs wandering off for some time and then returning. Bad weather

would usually bring the entire flock together, and they would all return to

Hero's Wetland. The river could be very swift and dangerous for the Geese after a

heavy rain. Hero's was a safe haven for them, as well as the place where they

were all born.

In any case, the period of learning,

schooling and molting

extends roughly from May until migration, which can be as late as December. The

females with goslings tend to gather together on the river and share duties in

watching the young. It amounts to a kind of baby sitting. The are occasional

disagreements about proximity of the goslings of one family to the family of

another pair. But these disagreements are mild. The community is composed of

families that are together, but at the same time separate. As the young are born

at slightly different times in May, they are of slightly different sizes. The

littler ones interact with the larger ones and all the goslings get to know the

adults, and learn which of the adults are friendly and which are not. But

in any case, the community holds together, despite differences between families,

arguments and disputes. The young learn to be part of the group before they

learn to fly. Learning to fly comes some months after

hatching. The parents molt in late summer as the goslings are growing their

wing feathers for flying.

In other words, the community of

Geese took one form during the mating and nesting period, where all the Geese

together, adults and juveniles, created an interlocking, almost honey-comb

like lattice of communal and cooperative relations. These relations composed the

flock into a union that helped the whole community to withstand stresses and

dangers. The form of the community changed after nesting, when the Geese all

moved to the river, and there the community sought safety for molting and the

education of the young. In July and August I would often see the Geese on the

river in groups of many adults and babies. Some of the parents would be

leading goslings of other parents, some would be leading their own, but all of

them would be loosely together. They rested and preened on pebble strewn

sandbars in the river. These months were an largely quiet and idyllic time for

them, with warm nights and long days, with the young growing stronger each day

and the whole flock gathering strength for migration and the coming winter.

To summarize, the creation of

discrete nesting spaces

for each pair during the period of sitting on the eggs had only one object, and that was the hatching of

the goslings. Once the goslings were hatched, the community reasserts its

primacy and the discrete boundaries between each nesting pair largely dissolve.

Their

main concern is not the creation of "territories" but rather, community.

The Geese immediately seek out other families and begin to gather together to

help raise each others goslings. The nesting occurs in late March to April, the

hatching in May, education of the young by the community goes on till the fall

into the winter when the whole group will migrate. Upon the return the following

early spring, these geese begin this cycle again.

Water into Air (detail)

THE YOUNG IN THE COMMUNITY

The community of Geese was composed of mated pairs of

various ages. There are the older adults who nest and younger pairs nesting for

the first or second time. Then there were the yearlings, who had been goslings

the previous year, and two year old juveniles, who had not yet found a mate. The

yearlings in the group experience a big change in their lives in their

second spring, a year after their birth. They are used to being attended to by

their parents. But as their parents begin a new nesting cycle, they begin pushing

the young of last year away, not far away, but away enough that the parents can

watch over their new nest. The yearling and two year olds are the

"troublemakers" of the community. They are too old to be babied, and too young

to know quite what to do. These young birds were the jokesters of the community

and the source of most of the trouble and humor. In most cases when there was an

altercation resulting in a bird being chased off, it was one of these juveniles

that was being chased off. This happened so often that I began to think that

much of what humans consider to be territorial dispute among Geese are actually

something different. The yearling Geese never go away far. In fact, they tended

to situate themselves right in the middle of all the nesting pairs, such that

they were still never far from their parents. The yearling Geese formed a kind of

sub-community within the larger community, and they created a kind of adolescent

society. They got themselves into a lot of trouble, but in the process they

appeared to be learning to be adults. A lot of the noisy altercations in a geese

community are actually a form of play. The play appears to be about learning the

limits of the community. The young Geese learn throughout the nesting period

what it means to nest and what the parents will tolerate and not tolerate. In

short, much of the behavior of the adults towards the yearlings was a kind of

schooling.

I was unable to tell if there was a sexual

division among the juveniles or if both females and males were part the group. I

suspect that both males and females were part of the this group. But I found it

much harder to tell sex differences among the young than among the adults. I

also could not distinguish clearly birds that could be yearlings and birds that

might be two years old.

Occasionally the young birds would

fly off together, in a kind of temporary migration formation, and return later. The nesting

adults would all set up a clangor at their return and the young would be chased

from nesting area to nesting area until they finally settled down in what seemed

to be a neutral zone, where they could preen and nap.

One of the most interesting things I saw the group of

juveniles do was play a certain sort of game. Hero's Wetland has a lot of dead

snags--- old trees, mostly sycamores and cottonwoods that have died because of

the wet conditions. Some of these dead snags have been dead for some years and

they tend to break off at points where one of the many woodpeckers who live

around Hero's have built a nest. The cavity nest weakens the tree. After a

wind storm I would sometimes find the parts of these trees fallen. A few of

these trees have broken off 30 feet or so above ground, leaving a very tall

stump, that had a sort of platform at the top, where the trunk had broken off.

The young geese liked to fly up to the top of the stump. Another young one would

see this and a commotion would begin. Another young goose would fly up to the

one standing atop the stump and try to displace the bird. It would succeed in

some cases and in others fail. The Goose who held the top of the stump would

then be the object of yet a third, forth or fifth goose, who would fly up and

try to displace it. this would go on for quite some time, with many of the

juveniles becoming involved. Sometimes two geese would try to displace the one

at the top. I saw this game played four or five times over the years. I do not

know if such games are unique to Hero's Geese or if similar or different games

are played in other communities. But it appears this this game had some

influence on the geese coming to build nests on top of some of the higher

stumps. As the younger geese aged they turned what they learned at play into a

means of increasing the safety

of their eggs. This is also what humans do, where games serve a similar meaning

as a way of children learning about living in a larger world.

Canada geese at Play and Nesting

(detail of Yellow Warbler painting)

It would be interesting to study distant but related

communities of Geese. This is the area of Geese relationships that I understand

the least. It was never clear to me why there were fewer geese after their

return from migration, and what the two-year or three-year-olds do exactly when they form

mating pairs. I suspected that the older geese at Hero's were aware of other,

perhaps related, communities elsewhere along the river system, perhaps miles

distant, and that some of the juvenile birds that left Hero's community joined these other communities.

I surmise that there is some understanding of the community of Geese that

live in surrounding areas. The juveniles would often go on what appeared to be

flying excursions in the fall. Five geese would disappear for awhile and then

return, for instance. Did they encounter other Geese communities on their

travels?

On occasion I wondered if some of the flocks of Geese

that rested at hero's wetland but did not stay were communities that lived up the

river somewhere or even further away. Do the young Geese that grew up at Hero's

and left return for a visit? But I

am speculating. I don't know. Nor could I determine how many of the yearling

Geese actually left the flock. it appeared that many stayed through the second

year and some became parents at Hero's. I don't know how many. Nor could I determine if any Geese from

other flocks joined the Hero's Geese. I suspect so. But I could not find out. Indeed, to determine this would require putting tags on the geese, radio collars

or other such invasive practices. I have no interest in doing this sort of

thing and think it of questionable ethics. The only real and ethical way to come

to know Geese more thoroughly would be to live with them for many years. With

time one gets to know individual Geese, as I got to know Hero's Geese and could

sometimes recognize them. It would be possible to recognize all the member of

the entire flock if one gave them that much time. But one would also have to

come to know adjacent flocks of Geese that might live miles distant. To know how

nearby communities of Geese interact with distant communities would be hard to

study.

COMMUNICATIONS

The complexity of the sounds Geese make is remarkable, and

much more subtle than seems to be indicated in some of the literature about

Geese. The sounds are often associated with body postures of various kinds,

which seem to modulate their meaning. For instance, with the behavior called

"head tossing" or "head flipping", the motion of flipping the head up and down

is usually made by the male in the direction of the female of a pair sometimes

with honks of various intensities. It seemed to signify mild irritation at

another goose, not part of the pair, that is nearby. But this is not invariable.

But the motion occurs so often especially prior to or during nesting, that it

seemed to have much more meaning than I was able to divine. I saw them use the

head flipping motion also when a group was about to take off. There were also

particular modulations of the familiar honk which appeared to mean that flight

as a group was soon to occur. Occasionally these organized movements weemed to be

the result of one goose as leader, but other times, the decision appeared to be

a group descision.

Head tossing is one

of many signals and sounds that Geese use to both communicate with their mates

and with the larger community of Geese. A Geese colony is a very noisy place. To

humans, hearing it for the first time, it seems chaotic and the Geese appear to

be aggressive and "territorial". But this is a very superficial understanding of

what is going on. The apparent cacophony of the Geese colony actually is the

sound of complex communications being voiced from nesting pair to nesting pair,

from adults to juveniles, and from Geese who might not be part of the local

community who have wandered in.

I have seen and heard a gander on

the pond call out to a group of ten or so geese flying hundreds of feet above

the pond, and as a result of the call the flying geese changed direction. It is

also clear, watching Geese who are migrating, that sounds that indicate

direction changes are a regular feature of their long distance flights. The lead

Geese call out changes to the Geese that fly behind them.

This ability to use sound to indicate

direction can be quite complex. For instance. In the Autumn, after the young had

all attained the ability to fly, the entire flock of some 90 birds, was dabbling

about the river on a warm day in two groups. One of the groups was up

river and the other down river a few thousand feet from the other group. A fisherman approached from up river. I was

standing between the two groups, watching them. Fisherman, intent upon the

catching and killing of fish, often neglect to respect the rights of birds to

their places. This fisherman was approaching the group of Geese up river. The

gander, I believe the gander from the pair I called Hero's Geese, seeing the

fisherman coming, swam down river towards the second group, who was watched over

by the 'wife' of the gander. As he called out to her he

began herding the flock that was with him, who were composed of mostly young

birds and a some pairs of adults.

The female, his mate, in control of the

second group down river, heard her husband's honks, and began gathering her

own group into closer proximity to each other, just as her husband was doing. Both groups understood by the

vocalizations, honks and hinks, that it was time to not just line up to begin

flying, but to face up river to do so. Hero's female then

began calling out, telling the first flock it was time to fly. Half of the flock

flew into the air and over a nearby bridge at the same time. The male, who had

gathered the rest of the Geese in the same area, took off with his group in an

identical manner and direction. it was all done in a matter of a few minutes.

The Geese all flew over the head of the offending fisherman and landed up

steam in a place they thought safer.

What amazed me about this event was that the pair

of Hero's Geese organized this flight almost entirely by using a series of

calls, honks and hinks. The sounds used were very subtle and were composed of

directions not just to the two groups of Geese but also to each other. The two

Geese communicated not only the need to fly to escape the fisherman, but where

they were to begin their flight, when and in what direction. They organized the two

groups of an entire flock into a take off position and all the geese facing the

same direction, and then accomplished the take off in a period of probably less

than two minutes.

This is no small accomplishment, given that 90 birds, most of

them very young, had to be told where to go, what direction to face and when to fly. In order to

accomplish this the seemingly simple sounds of the geese had to express

intention and purpose and involved planning for an entire group, organizing where to move, what direction to face and when to fly. This is a very complex

set of directions and intentions, and certainly as complex as anything humans

do, in terms of requiring foresight, managing groups, as well as reasoning and

planning an event in the near future that will help the group as a whole.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine that two adult humans could organize 90 children

and young adults to move in a stated direction and do it in less than tow

minutes. Moreover, all this was done without what humans call language, or rather, it

was done with a kind of non-linguistic language that is different in kind from

anything humans call language, but in no way "lesser" than what humans call

language.

The mistake that humans typically make in

regard to non-human communication is that human language is always compared to

non human sounds. It is always humans, with their human centered concerns that

do the comparing. No surprise that the conclusion is always that human language

is superior to anything in nature. But this is a speciesist fallacy. One can

tell nothing about the sounds of birds or animals without first knowing the

context of their lives and actions. It is impossible to know or say anything

realistic and accurate about non-human sounds without first completely immersing

oneself in the lives of the animals or birds one would like to understand. This

is not easy to do, and above all requires huge amounts of time. If I had not

spent three years closely watching the flock at Hero's I would not have been

able to perceive the intelligence and insight of their behavior on the river

relative to the threat of the fisherman. This is not to say that I now

understand everything Geese are saying in their complex interactions. Hardly. I

understand only fragments of their speech and how they live in the world. But I

discovered that these are not only marvelous birds, but that their society is

rich and complex and as full of intrinsic value and worth as the lives of human

beings. But they are very different than human beings and this difference

demands our respect. The abuse that humans deal out towards Geese and most of

the other kinds of beings on earth is evidence, not just of the limited and self

centered nature of human language, but of the myopic lack of respect and

insensitive unwillingness to listen to the concerns and lives of other kinds of

beings. As the poet Pablo Neruda wisely asked, "how is the translation of their

languages arranged with the birds". Indeed, birds do not appear to need

translations of what they say. Birds of different kinds appear to understand

each other well enough. far better, in many ways, than human-animals who speak

the same language often understand each other. It makes one wonder.

Copyright © 2002 Mark Koslow.

All Rights Reserved.

|